King Felipe III's Expulsion Decree of the Valencian Moriscos was made public on the 22nd of September, 1609. This date thus became a historical and cultural turning point for the Kingdom of Spain.

With the Expulsion Decree, a total of 127,000 Valencian Moriscos were given six days to leave their houses and lands and begin a very uncertain future. It is estimated that the entire Valencian territory had around 350,000 inhabitants at the time and so the Moriscos accounted for more than a third of the total population. However, according to some authors, such as A. Furió, the percentage was even higher in the case of certain areas, including the region of La Marina Alta, with the population of New Christians or Moriscos being as high as two thirds of the total.

More concrete data, extracted from Lapeyre's work, puts the total number of inhabitants ousted from the whole peninsular territory at an estimated 272,140: 43.16% were from Valencia, 1.36% from Catalonia, 22.35% from Aragon, 16.40% from Castile, 4.98% from Murcia, 11% from Andalusia and 0.75% from Granada. Just by glancing at the percentages it is easy to deduce the magnitude of the demographic decline, throughout the kingdom, created by this political and religious decision. The expulsion of the Moors had a great impact upon 17th-century Valencia, affecting several aspects of life. From an economic point of view, the inflation of the currency called “el velló” should be highlighted, being due, in part, to the counterfeit coins that the Moors had been minting, and above all there was a crisis faced by the nobles who were not able to collect money from the feudal lords, with loans which could not be paid back because the lords were highly indebted and suddenly had no one to cultivate the land. As for agriculture, with the expulsion of the Moors, shortages began to appear regarding products such as sugar cane, rice or wheat due to the fact that they had been the traditional producers of these types of crops. Of course, this condition accelerated the start of a diversification process in Valencian agriculture which would continue well into the 18th century. It is also important to note that the dimensions of the plots of land began to change as a result of the expulsion, with the elimination of plots with extremely small surface areas and thus allowing an improvement in conditions for farmers with medium-sized plots. Finally, there are the demographic consequences already mentioned earlier, from a numerical point of view. To illustrate this situation, we can quote the contemporary chronicler Escolano who, when talking about the Kingdom of Valencia, wrote that “the most flowery region of Spain had become a dry and neglected desert”. The great loss of population in these territories brought about the need to search for solutions, especially since the lords realised that the migration they had expected —coming from diverse places, such as Castile or Europe— had not been well-received. This occurred, on the one hand, because the territories that had previously been populated by the Moors were those with less attractive conditions for new settlers, due to the fact that they were the most mountainous and arid lands. And, on the other hand, because the population movements that were taking place between the various Valencian nuclei were not giving good results, since all the Valencian peasants that came to repopulate this territory had previously depopulated their own villages. The solution came from the lords themselves, with repopulation based upon a plan they had come up with previously. In our region, the remedial action was undertaken by the sixth Duke of Gandia, Carles Borja i Centelles, whose initiative was followed by most of the other lords, with the intention being to bring new settlers from the Balearic Islands due to the fact that the conditions of the peasants there were quite complicated with a very notable saturation of the cultivable land. Some authors attribute the success of the Majorcan repopulation to an alleged interest of the viceroy of Majorca, Joan Sanz de Vilaragut, Lord of the Barony of Olocau, who was also affected by the situation, bearing in mind that he also had domains in the Valencian area. When he died, the strategy was suddenly at risk but Carles Coloma, who was also Valencian, became the new viceroy of Majorca and the continuity of the Majorcan repopulation was thus guaranteed. The new settler strategy, now Majorcan, seemed to begin to work, so much so that in a meeting held by the reverend of Muro (Majorca) on the 22nd of September, 1610, he explained that “this time the whole world is going to the town of Valencia and the houses will come to be worth nothing”. Amongst the new settlers there was a clear Majorcan predominance, followed to a lesser extent by peasants from Ibiza and Menorca. The process had two main characteristics. First of all, it was a plan conceived by the lords, as already mentioned, meaning that they took advantage of the poor conditions of the Majorcan peasants so as to make up for the lack of cheap labour, with the Majorcans being more malleable than the potential Valencian settlers. And, secondly, the new repartitions and land conditions were agreed upon by way of a document called the settlement papers, signed by both interested parties, the new inhabitants and the lords. These were collective feudal-based contracts for the repopulation or colonisation of a place (and for the cultivation of its lands), made between the lord and the settlers, in which mutual rights and duties were generally expressed. They were the regulatory documents of the first migrations from the Balearic Islands or other Valencian areas and date mostly from the period between 1610 and 1612, although it is also possible to find some from as late as the middle of the 18th century.

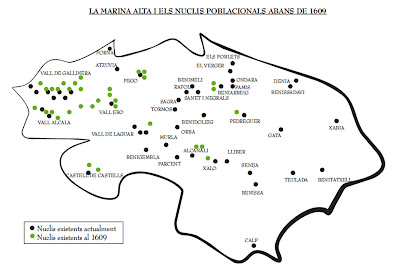

It must be taken into account that, before the expulsion, of all the villages and towns within the area known as La Marina, the inhabitants were predominantly old Christians only in 6 nuclei (Pego, Xàbia, Dénia, Teulada, Benissa and Calp). Another 3 had a mixed population (Murla, Ondara and Forna) and the rest were inhabited by New Christians or Moors. Not all the documents have survived the passage of time or perhaps some even remain to be discovered, but according to the settlement papers that we know of so far, as reported in the studies undertaken by J. Costa Mas (2006) after analysing parish archives, there is information about the following municipalities: 1.- La Vall de Gallinera: Settlement papers signed by Matheu de Roda, procurator of the Duke of Gandia, and 78 heads of Majorcan families, in Benialí on June 10th, 1611. 2.- Parcent and Benigembla: Settlement papers signed in 1612, with new settlers from Pego and Murla, and also from the Balearic islands. 3.- L'Atzúbia: Settlement papers signed by lord Francesc Roca and six Majorcan families, dated August 26th, 1611. 4.- Negrals: Contract signed by lord Jaume Pasqual and families from Pego, on August 31st, 1611. 5.- Ondara: Municipal charter dated August 8th, 1611, in which even the municipal positions were distributed (such as justice, juries, etc.) and which contemplated the obligations of the vassals with regards to the lord's monopolies, such as the mill, the oven, the butcher's, the store, the tavern, the bakery and the weight room, as well as the brokerage house. 6.- Pego: The Duke of Gandia brought 25 settlers to the farmhouses of Benumeia, Favara and Atzaneta. 7.- La Vall de Laguar: The municipal charter of the Barony of Laguar, where 27 settlers arrived, was signed on June 14th, 1611, by the Duke of Gandia. 8.- Sanet and Sagra received people from Granada, Valencia and Mutxamel. 9.- Negrals received 6 settlers from Pego with the municipal charter of 1611. 10.- Benidoleig: Land granted to 7 families from Majorca and 4 from Pego. 11.- Forna: Municipal charter signed on September 2nd, 1611, by Àngela Pallàs i Lladró and 8 Majorcan families. 12.- Tormos. 13.- Pedreguer: Charter signed in 1611 by the lady of Pedreguer, Francesca Alpont i Pujades, and the new settlers of Matoses and Pedreguer.

Despite everything, the settlement papers were only the beginning of a repopulation process that continued for at least a century before managing to provoke a demographic recuperation of the losses that had occurred as a result of the expulsion. And so it was that the “Majorcanisation” process began. The flux of people from the islands lasted throughout the first half of the 17th century, entering through coastal ports such as Xàbia and Dénia, which became places of reception and passage towards places to be settled in the La Marina area, in an attempt to improve their conditions and find new land to cultivate. However, even with the Majorcan repopulation spreading throughout the interior valleys of La Marina, a large number of farmhouses remained abandoned and became places that were forgotten and never inhabited again. So much so that perhaps this is one of the regions where the greatest concentration of abandoned villages has been preserved, and this happened due to the harshness of the habitat and due to the fact that it is a very isolated area, surrounded by several mountain ranges and with no easy natural outlet to the sea. These valleys (Gallinera, Laguar, Ebo, Alcalà, Pop, Xaló and La Rectoria) were Moorish, since the Muslim population was relegated to the interior after the Christian conquest, far away from the large fertile valleys of the coast and with the consequent difficulties of movement due to not being close to the main road network of the coastal plain.

It is easy to observe on a map of the region how the quantity of population centres declined sharply after the expulsion of the Moors. Before that moment, the map would have had a total of 77 towns and villages, listed as follows: the villages in La Vall de Gallinera were L'Alcúdia, Benialí, Benistrop, Benimamet (lower farmhouse), Benimahomet (upper farmhouse), Benimarsoc, Benirrama, Benissili, Benissivà, Benitaia, Bolcàcim, La Carroja, Llombai, Alpatró, Ràfol and Solana; in the valleys of Alcalà and Ebo, Alcalà de la Jovada, Atzuvieta, La Roca, La Queirola, Beniaia, Benialí, Rafalet de Benixarcos, Capaimona, Benijuart, Bisbilan, Benicais, Serra, Solana; in the Pego area, Atzaneta, Benumeia and Favara; in Castells de Castells, Ayalt and Vila; in the valley of Xaló, Benibrahim and Llíber; in the Beniarbeig area, Benicadim and Benihomer; in Parcent, Bernissa; in Pedreguer, Matoses; in the valley of Laguar, Ixbert, Fleix, Campell and Benimaurell; in Alcanalí, Mosquera and Beniaia; in Ondara, Pamis; Benissa; L'Atzúbia; Xàbia; Calp; Gata de Gorgos; Dénia; Senija, Murla; Sagra; La Llosa de Camatxo; Tormos; Orba; El Verger; Ràfol d'Almúnia; Benimeli; Sanet; Negrals; Benidoleig; Els Poblets (Setla, Mirarrosa and Miraflor); Beniçadavi (currently known as Jesús Pobre); Forna; and Teulada. It is here, within the inland valleys, where one can find the best examples of the devastating demographic situation that the Kingdom of Valencia went through, and where it is possible to truly observe the Moorish constructions that were once a part of our history and that today remain as a sort of link to a not-so-distant past.